Overview

This post is about the most effective pattern I’ve seen used to present people with data. This pattern has come up at every company I’ve worked for, and replaced a lot of other less disciplined approaches that didn’t work as well. In this post, we will call it the Summary-List-Detail pattern because it consists of presenting users with the same underlying data in three different views: the Summary view, the List view, and the Detail view.

TL;DR: The Summary-List-Detail pattern consists of a) curating a single data table to underlie all three views b) building a summary view that shows aggregated data, c) building a list view that shows individual data items, but with a lot of filters to let the viewer select just those items they care about and d) building a detail view that fully explicates a single item.

The reason this pattern works so well is that it’s the best way to ensure consistency of the semantics of your data at different levels of detail. In other words, all your views are telling the same story, and they agree with each other. The particular Summary, List and Detail views are also a great way to reduce duplication of work because these three views can be reused the exact same way in a wide variety of contexts.

Read on to find out about the 4 artifacts you’d need to build to implement the pattern: The Summary view, the List view, the Detail view, and most importantly, the Underlying Data Table. After that, we’ll go into detail on the benefits of using this pattern, and discuss how AI-agents fit in.

Example Data Items

The rest of this post will refer to specific example datasets to illustrate its points. Each example consists of a set of “data items” to present to our end users. Here are the examples:

- Biological Experiments: Each “data item” is a scientific experiment we should conduct in our lab.

- Strains of Yeast: Each “data item” is a particular strain of yeast to be used in some biological experiments.

- Freight: Each “data item” is a contract with a freight carrier to load goods onto a truck at one location and drop them off somewhere else.

- Box Sorting: Each “data item” is a cardboard box filled with goods. The box needs to be sorted to a particular warehouse based on where and when we expect the products inside to be sold.

I picked these examples because they illustrate my points and they’re what I know the best, but the Summary-List-Detail pattern seems general enough that it should work well for a very wide variety of other kinds of data items. You can read the rest of this post with the words “data item” substituted for whatever kind of data you’re thinking of presenting to your end users.

The Underlying Data Table

The first, and most essential part of the Summary-List-Detail pattern is the underlying data table. This table isn’t directly visible to the end user, but it’s normally the most important and most challenging piece of the whole pattern to get right. Very importantly, each of the three views (Summary, List, Detail) should be a relatively thin presentation layer on top of this underlying data table.

Joining data sources together

The underlying data table will often be the result of joining several sources of data together.

To give a really specific example, let’s say we’re presenting the Box Sorting data. We’ll call the underlying data table behind our views the box table. In order to produce that table, we will need to join together a variety of different sources of information. For example, we have one table of box labels people may have printed, one table of box scans that confirm the existence of a labeled box, one table of box dimension scans giving the length, width, height, weight of each box, and then a whole host of box-XXX-event tables that record relevant events that took place in the context of a particular box.

Underlying data tables usually follow a similar pattern to the box example above in which we’re deliberately joining together and simplifying a potentially very large number of distinct data sources about the same items.

Existence and Uniqueness of Data Items

Two of the most important concerns regarding the underlying data table are what you would call “existence” and “uniqueness”.

Existence

The “existence” concern is that we have to come up with a definition of which things should count as a “data item”. To go back to the example of the box table above, do we a) include only boxes that we can confirm were physically constructed or b) include any box identifier that we ever generated? Usually, there’s some question about whether we should include things in this table when they’re an idea v.s. when we’re sure they really exist. In the example of Biological Experiments you might wonder whether to include in your underlying experiments table just those experiments that have been started, or any experiment that has been proposed.

My recommendation is to take a very broad definition of existence. We can always add a few columns that make it easy later on to filter out the items we don’t care about. e.g. create an experiment.is_started or experiment.started_at column that helps filter for experiments that have actually been started.

Uniqueness

The “uniqueness” concern is the question of when and how to deduplicate items in the table. Sometimes this is straightforward, but other times it can be very complicated. In the case of Strains of Yeast, we might choose to call two strains the same if they were produced by the same biological process and designed to be genetically identical. But alternatively, we might instead choose to include a separate row for each time somebody picked a separate bacterial colony. (For context, a lab will often pick several colonies that they hope will contain the same strain of yeast, but in case something goes wrong or they get unlucky, it’s possible that the different colonies might be genetically distinct.) Picking the right kind of deduplication for a yeast_strains table can be a rather complex task, and might involve a lot of discussion about how we like to run our experiments and how to manage the risk of mistakes.

If you’ve worked with enough data tables, you may be used to how complex these questions of deduplication can get. (Ask someone who works on google books what makes two books “the same” and you could be in for a several hour discussion!) This post will not resolve all those questions, but for our purposes, we should say that we want to have all those questions answered in one consistent manner when we’re done designing the underlying data table. Once there’s a single agreed definition of uniqueness, then each of the Summary, List and Detail views will be operating under the same definition.

“Official” column names and their semantics

For this section, let’s again start with a specific example. We’d like to add a box.arrived_at column to our box table to record the time a box first arrived in our warehouse network. It seems like a simple enough column at first, but when we start to dig into it, things get more complicated. Should we use the time the truck driver arrived at the gate outside our warehouse and checked in with the attendant? Or should we use the time the truck was unloaded? Or the time a label on that box was first scanned at one of our warehouses? While normally most of these timestamps are probably going to be pretty close to one another, sometimes the differences do matter, and as good custodians of the data we don’t want to leave too much ambiguity about what our columns mean. The nice thing about working on an Underlying Data Table is that the table itself is never presented directly to our end users, so there’s usually not much harm in adding a separate column for every particular meaning, just as long as we’re careful to document the whole thing. So in the example above, perhaps we create columns for box.arrived_at_gate_at, box.unloaded_from_truck_at, and box.first_scanned_in_warehouse_at. We then write up good docs on exactly what those columns are supposed to mean and where the underlying data comes from. We probably also want to add a box.arrived_at column that’s somehow derived from the other columns and works best for people who are not all that interested in the particular details of how we first determined that the box had arrived.

In general, the point of documenting “official” column names is that we resolve all the ambiguities about what our column names mean, we document the columns clearly, and then use the same column definitions consistently across the Summary, List and Detail views. We give the columns distinct, carefully chosen names. We highlight which column names are the most important to our end users and which ones are only necessary for digging into the internal details. These “official” columns are going to form the basis of all the statistics on the Summary, List and Detail reports. If ever a person (or an automated AI agent) is looking for clarity on the precise semantics of one of those reports, we should be able to refer them to the documentation of our underlying data table.

Lastly, I should point out that the things listed above that make for a good underlying data table also make for a good table generally, even outside the context of the Summary-List-Detail pattern.

Summary View

The role of the summary view is to present aggregate statistics about a potentially very large set of data items. The summary view is great for helping us spot anomalies, for reassuring us that the business is running smoothly, and for helping forecast out trends into the future.

Importantly, the amount of data displayed in summary view shouldn’t depend at all on the number of data items. So regardless if we’re running e.g. 10 experiments per day or 10,000 experiments per day, the summary view should render just as fast and display about the same number of data points.

Normally, the summary view is some kind of dashboard with a lot of charts that display one data point for each unit of time. So this is where we’d see charts of things like e.g. “total orders per day” or “p90 time from experiment started to experiment finished”, “failure rate of experiments per week”, or “maximum running time of an optimization job per day”. They also tend to have pie charts, scatter plots, or really any kind of data visualization that’s useful for conveying high level summaries of large data sets.

The summary view typically displays very little information about individual data items, though perhaps it might contain a table or two to help us notice outliers. For example: “Top 10 experiments that took the longest to run this week” or “Boxes at the sort center with no activity in the last 48 hours”.

Calculating the data for the Summary View

The data for most of the summary view is almost always calculated by a simple aggregation of the underlying data table. e.g. a single SQL GROUP BY or pandas groupby operation. Also, the names we use for the displayed statistics should be very closely related to the names of the columns in the underlying data table, ideally using the same exact name with some prefix or suffix to indicate how they were aggregated. e.g. if we display a total of experiment.minutes_on_instrument from the experiment table, then we should call it something like “Total Minutes on Instrument” or divide by 60 and call it “Total Hours on Instrument”. Using this kind of naming convention is critical for communicating a sense of consistency between the Summary view and the other views.

As with all the other views, the Summary view is meant to be a very thin presentation layer. If you ever find any logic in the Summary view that’s more complex than a single group-by with some aggregates, consider moving that logic into a new column in the underlying data table.

List View

The role of the list view is to display a list of data items meeting some search criteria and to let the user compare them to each other.

Visually, the list view always looks like some kind of table or list of items. Each item in the list should have a link to the Detail view for that item. Often, the filter criteria are displayed at the top and often there are controls to let the user modify the filter criteria. The key decisions we need to make when designing the List view are a) which columns to display and b) which filters to expose.

Which columns to display

While it’s hard to say in general which columns to display in the List view, here are a few principles that may help:

- Put the most important columns first.

- If there are several closely related columns, we should probably just display one of them. If you really want to keep the others, put them later in the list, or otherwise hide them in some way.

- It’s usually good for one of the first few columns to be some kind of prominent timestamp that gives the user a sense of the rough time frame that the item pertains to.

Which filters to expose

Again, which filters we use really depends on the context. A few pointers:

- Try to avoid using redundant filters or using two very similar filters.

- It’s good to have an easy way to filter by the rough time frame. e.g. A

start_atand astop_atfilter tend to be very useful. - Some filters might be set based on the context in which we’re using the List view. e.g. When we display a list of experiments on the detail page for a particular instrument, we’ll want to automatically filter by instrument, and probably hide the instrument filter and the instrument column.

One last note, it’s a bad sign to have substantial logic in the List view for calculating the columns or applying the filters. If that happens, please consider moving that logic out of the List view and into a new column in the underlying data table.

Detail View

The detail view is the go-to place to get all the information an end-user would ever want to know about one individual data item. Because the scope of the Detail view is so narrow, it’s a great place to put highly detailed and specific information. It normally looks like some kind of dashboard with a big prominent setting up at the top to let the end user select the unique identifier of the particular data item to display.

Naming

For a model named “X”, I recommend always calling the Detail view “X Detail”. e.g. “Box Detail”, “Experiment Detail”, “Freight Shipment Detail”. Some people might prefer “X Dashboard” or some other convention, but if you’re going to use a different convention, I recommend you pick just one convention and stick to it consistently.

Detail View Best Practices

Some practices that seem to work well on detail views:

- The top of the detail view should display the same information that’s displayed in the List view, but for just that one data item. Also, the detail view tends to have much more available space, so we might decide to display some of the less important columns that are hidden on List view.

- A Detail view is a great place to incorporate List views for related data items. e.g. “Strain Detail” would incorporate an embedded “Experiment List View” filtered for experiments on just that particular strain.

Event Tables / Timelines

For certain data items, the people looking at them are usually interested in seeing a timeline of events that were relevant to that item. This pattern comes up so much that I think it’s always worth considering adding some kind of “timeline” or “event table” to any Detail view. A good timeline presents a list of events, in chronological order, with some kind of event_type column indicating what it was that happened.

When it comes to picking the specific types to use for events, again it depends on the context, but here are a few examples:

- For the Biological Experiments example, we could have types like

EXPERIMENT_CREATED,REAGENTS_ORDERED,REAGENTS_RECEIVED,EXPERIMENT_STARTED,EXPERIMENT_ERROR,EXPERIMENT_FINISHED. - For the Box Sorting example, we could have types like

BOX_CREATED,BOX_SCANNED,BOX_SORTED,BOX_STAGED_FOR_PICKUPe.t.c.

Sometimes, there are certain columns you can add to the event table that make perfect sense for any type of event. e.g. every event in a box_event table could use a box_id column to identify the box, a warehouse_id to identify the warehouse at which the event took place, and an occurred_at to indicate the time the event took place. It’s good to add such columns to the event table. There are circumstances, however, in which a column is only really relevant for certain event types, but not others e.g. a box_event.carrier_id only makes sense for box events that involve a shipping carrier. I’ve seen a few approaches to handling those kinds of event-type-specific columns. If there are not too many event-type-specific columns, then it’s fine to leave them blank when they don’t apply. If there are a lot of event-type-specific columns, however, displaying all of them can make the events table rather unwieldy. In that case, maybe we display just the most important columns, but add a link to each event that takes you to a Detail view for just that one type of event.

The Detail View as a Starting point for Discussions

At the start of a discussion with a coworker, you can share a link to a Detail view to help anchor the discussion in shared data. e.g. “Hey Joe, any idea why it looks like this experiment has been running for over 2 days?” or “Hey freight team, I see that this freight shipment was supposed to arrive in Chicago but it looks like it actually arrived in Texas. Has someone been re-routing our freight shipments?” If you’re going to get into a discussion with your coworkers about a particular data item, it’s extremely helpful if at the start of the discussion, everyone agrees where to go to fetch official records about it.

Why use the Summary-List-Detail Pattern?

Here are some of the benefits to organizing your data and presenting it according to the Summary-List-Detail pattern:

Easily Find Specific Examples Contributing to a Trend/Anomaly

One of the top uses of any summary view is to spot trends / anomalies in the data and respond to them ASAP. You’ll see that some aggregate statistic on the summary view is going either up or down. After you spot the trend, however, you then need to find a reason for the change. One of the best ways to do that is to bring up the List view, filter for the cases that are causing your anomaly, and try to spot the cause there. If it’s still not clear, then maybe you pick a couple specific instances from the list view and review their Detail views to see if it shows up there.

Examples

Biological Experiments: The overall number of “failed” experiments increased substantially yesterday. We pull up a list of yesterday’s failed experiments and another list of today’s failed experiments. Today’s list is a lot longer. We scan today’s list of failures and quickly realize that most of them were run on a particular instrument. We physically inspect the instrument and find that it’s either miscalibrated or broken. We recalibrate the instrument or take it offline until someone can service it.

Getting people on the same page.

Often, your organization has some kind of shared responsibility that cuts across several teams. At the same time, each team is ruthlessly focused on prioritizing just their most important work, and so if something looks like it’s someone else’s problem, they’re naturally going to deprioritize it. The situation you really want to avoid is one in which each team has their own version of the data, and each team believes that they’re not making any mistakes, but somehow a problem shows up, and when you try to figure out who’s responsible for fixing it, everyone points their finger at someone else.

Examples of the situation we’re trying to avoid:

Freight: The team booking the freight believes that 98% of their pickup drivers arrive on time, but the team operating the warehouse believes that only 85% of the pickups happen on time. Who’s responsible when the customers are upset about delays? Without consistent reports, each team will naturally want to blame the other one.

Box Sorting: The team shipping the boxes says that there were 45 boxes on a particular pallet, but the team receiving them says that there were only 38. Each team believes they didn’t lose any boxes, but there are still 7 boxes missing. Who’s responsible for the missing inventory and what do we do about it?

The Summary-List-Detail pattern helps to clarify those responsibilities because it sets up a standard set of columns that everyone looks at. To get it to work well, you’ll have to make sure that all the teams are using the same underlying “official” columns to calculate their result metrics. e.g if there’s a single freight_shipment table with a single freight_shipment.had_ontime_pickup column with a clearly defined semantics, then the two teams looking at it will be forced to agree on the rate of on-time pickups. Beyond that, it makes it easy for people on different teams to review examples together: the warehouse-operations team can point the freight-booking team at a specific instance of the Freight Shipment List view showing exactly the pickups that were late last week and ask for some clarity as to what’s going on. A discussion like that, centered around shared data, is well positioned to help the teams get to the root of their problem.

List View Re-Use

List views are super useful, and the same List view is likely to be relevant in a lot of different contexts. Ideally, you’d like to build out most of the list view just once and then reuse it in each of the different contexts.

Examples:

Biological Experiments:

In the following three contexts, we’re going to need to display a list of experiments, and for the sake of simplicity we’d really like to be able to use the same List view each time:

- Lab operators would like to look at a detail page for a particular instrument in the lab. On the detail page for the instrument, we should show them a list of upcoming experiments that will run on that instrument.

- On the detail page for a particular strain of yeast, we also want to show a list of experiments, but this time it’s just those experiments that gathered data on that strain of yeast.

- On the detail page for a person working in the lab, we’d like to see a list of all the recent experiments they’ve run.

How Summary-List-Detail relates to AI agents

Surely any blog post about presenting data to users wouldn’t be complete without a mention of genAI. So how do Generative Artificial Intelligence and Large Language Models fit into this pattern?

For one, automatic “data analysis assistants” may help do a lot of the work of building those 4 data artifacts. As that happens, it’ll just get easier and easier for people to model and present their data using the Summary-List-Detail pattern.

Another big question is whether it will even be necessary for people to create these kinds of views. If automated data analysis assistants can identify trends and anomalies in the data on their own, why bother building all these views in the first place? While we definitely do see people pushing AI agents to spot and explain trends in data on their own, it’s still very difficult for the people using them to trust any of their conclusions. The agents are great at coming up with plausible sounding explanations, but sometimes they’re just flat out wrong, or they’re hallucinating, or they’re missing some important context that only the people at the business know. Do you really want to make an important business decision based on the unvalidated conclusions of an AI agent? If the people at a company are ever going to trust the explanations of an AI agent, they’re going to need some way to review the same data agent used and see for themselves whether it actually supports the claim that the agent is making. So regardless of how good these AI agents get at doing the data analysis on their own, there’s still going to be a need for people to review well presented views of that data, and the Summary-List-Detail pattern will remain a great way to present the data to people for review.

Wrap up

The Summary-List-Detail pattern is a highly effective way to present people with consistent views of the same data at every level of detail. The Summary view tells them what they need to know about the data in aggregate, the List view lets them find specific examples and compare them succinctly, and the Detail view is for diving deep into everything you’d want to know about any single data item.

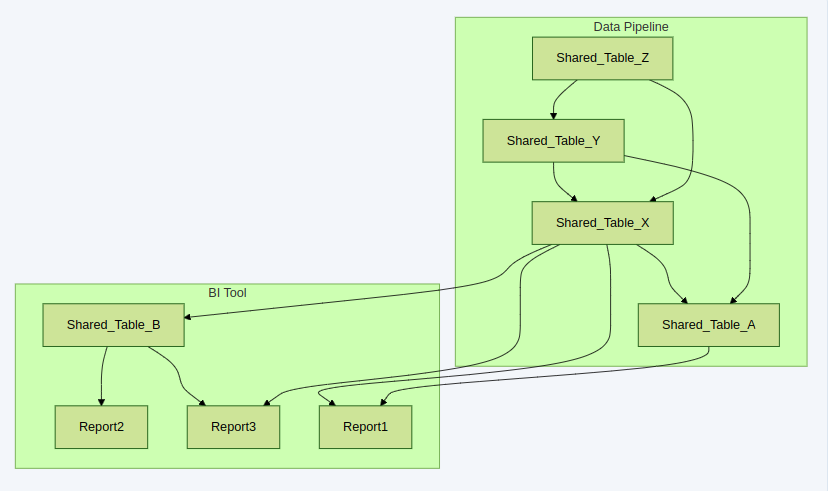

In case you’re looking to implement this pattern, I highly recommend taking a look into Quodor Data and getting it touch with us! Quodor is developing a new BI tool to help people draw useful conclusions from their internal company data and it’s perfectly suited for building all the artifacts you need to make the most out of the Summary-List-Detail pattern. But whatever tool you use to implement it, this pattern is quite universal and should work well in just about any context.